For coal miners, so much depends on how we think about and use this black rock. Photo Pavlo Fox 2014

July 1, 2017. Among the many dramatic yet predictable executive orders in the first several weeks of the Trump Administration was this one: allow coal companies to again sidestep the intent of the 1972 Clean Water Act and let acid water from coal mining continue to damage Appalachian streams. Something intended to help the miners—the return of jobs to an industry suffering from a long downturn—will not come to pass and, tragically, the executive order will only bring more sorrow to the mining towns of West Virginia, Pennsylvania and Kentucky.

How is this possible? We have to reach back into the history of coal mining to understand. It used to be mainly an underground operation—vertical shafts going down to reach the coal seams, and horizontal shafts following the seams wherever they might lead until it was no longer economical to dig that seam. In the 1960s coal companies also began removing the tops of mountains that had coal in them using massive earth-moving equipment, piling the mountaintops in nearby stream valleys, and digging the coal out with a front-end loader the size of a small house. This reduced costs because you needed fewer coal miners, making it more profitable to mine coal. Meanwhile, in mines still underground, mining continued its march toward greater efficiency through mechanization, and also dumped its rock spoil in valleys.

Big machines make mining safer and more efficient, but you don’t need as many miners–50,000 are working today, down from a peak of 860,000 in 1920. Photo Peabody Energy Inc. 2015

Aside from the wholesale removal of mountaintops, which, as you can imagine has a few unattractive aspects, the rock around many coal seams is laced with pyrite, a sulfur-bearing rock. When rain hits that rock, the pyrite transforms the rain from a neutral liquid, like tap water, to an acid able to damage living tissue. This shouldn’t be a surprise since we all were cautioned about sulfuric acid in our high school chemistry class. Underground mining has its own drawbacks, too—undermining foundations and affecting water flow in streams. Both mountaintop and underground mining can damage streams by making them acid with the rock rubble they place in valleys.

You can see the effect of stream acidification on aerial photographs from the mining districts. Orange streaks in valleys are acidified streams. There aren’t too many species on the planet that can survive in acid water…bacteria like those in Yellowstone’s hot springs, maybe…but no snails, no clams, no dragonfly or mayfly larvae, few if any fish—none of that. All those things disappear and you are left with a largely lifeless orange slash on the landscape. The orange coating on stream bottoms and banks is a side effect, when iron dissolved in a stream coalesces, settles, and attaches to stream banks and rocks. Bottom-dwelling insects, the base of stream food chains, can’t tolerate the conditions. Having such a stream in one’s backyard can’t be a good thing.

Orange-tinted Shamokin Creek, Pennsylvania. Upstream mining acidified the water, causing dissolved iron to coalesce and coat the rocks and stream bottom. Photo Jake C 2014.

Since its inception the Environmental Protection Agency, as part of its charge to enforce the Clean Water Act, has developed rules to explain how the law was going apply to specific situations, like mining. These rules would direct mining companies, for instance, to stop dumping acid-creating rock rubble into streams and to prevent acid runoff leaching into them. To do that one has to build a containment pond, or tailings basin, and treat the water to reduce its acidity. Of course the mining companies hated that because it cost money, and mining, like landfills and any industry done in bulk, deals in profits of pennies per ton. Many, many tons must be sold to pay for a tailings basin that won’t acidify a stream.

Despite having the legal authority to do so, the Environmental Protection Agency never got around to finalizing the rules until the Obama administration, and did so in the last moments of his second term. One of the Trump administration’s first acts was to retract that EPA rule so coal companies could continue to pile acidic rock in streams or discharge acid water directly into them.

The damage to the environment is, yes, something to be upset about, but what seems more tragic to me is the human drama playing out. Some coal miners must suspect that allowing coal companies to acidify streams in their own back yards won’t bring the jobs back. But for the moment that straw of eliminating regulations is the only thing within their grasp. They know that coal is up against stiff competition from other ways of getting energy. Coal’s biggest enemy, natural gas, emits far less carbon per megawatt hour generated, requires cheaper pollution control devices at the smokestack, is easier to transport, requires no large storage areas, and at the moment is about the same price per megawatt hour as coal.

Power companies across the country are tearing down their coal-fired power plants and installing natural gas energy production facilities. I watched the demolition of one of them several years ago in St. Paul. The massive facility, towering black piles of coal, and a 250 foot tall smokestack are all gone. Instead there is a compact, low-slung building with two squat smokestacks. All the extra ground has been turned into a park with a bike path. Meanwhile, solar and wind powered energy continue to be produced at ever-lower costs, predicted to be cheaper than coal in the next several years.

The idea that coal companies will share with workers the small savings they get from not having to properly manage their acid runoff is a pipe dream. Likewise, coal companies will do their best to avoid hiring new workers if they can increase production by increasing efficiency. No company in America, except ones owned by employees, would turn a windfall back to workers. That windfall will go to dividends for shareholders, bonuses for top managers, investment in automation (because labor is the biggest cost in every business), and cash reserves to bolster the stock price. That is the natural way of capitalism, as Thomas Piketty pointed out with his equation, r > g. (The rate of capital growth is always greater than the rate of growth of the economy—in other words, owners of invested capital get ahead much faster than those who earn their living by wages.) The income gap grows because the owners reward themselves first, and everybody else, if there’s anything left, gets what’s left.

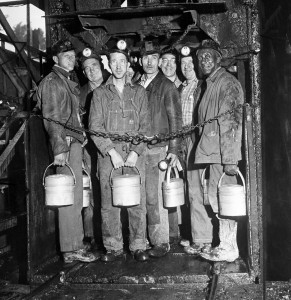

In 1946 when this photo was taken at the Frick coke mine in Pennsylvania, there were 75,000 miners in the state, and 550,000 nationwide. Photo Edwin Morgan (Bettmann/Corbis) 1946

So President Trump threw the coal miners a meatless bone as a reward for their vote, despite no real turn-around likely in the decades-long decline of the industry. But I imagine that as great a tragedy for coal miners and their families as losing their livelihood, is to live daily with cut-off mountains, spindly trees struggling on poor soils, orange streams, cracked basements, and the permanent environmental ailments of the coal industry. Surely there is a better way. Surely the nation can help its fellow citizens in Appalachia transition from coal to a new economic basis without sacrificing the quality of the land and water. – Kim