“Après moi, le déluge” – Poor decapitated Louis the 16th could just as well have been talking about the re-construction of Highway 8, rather than the French Revolution. Signs promising a bounty of 2.5+ acre homesites have sprung up since the road was finished. Photo by Kim Chapman

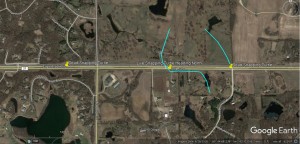

December 27, 2017. It’s been fifteen years since I started commuting from St. Paul to my country office, and it’s time to take stock. In that time Highway 8—or 220th Street in the extended Minneapolis street grid system (evidence of the grand vision the city fathers had)—has acquired these items.

- A six-lane bridge with cloverleaf over Interstate 35

- A wider, straighter thoroughfare through rolling, wetland-studded countryside

- A two-lane roundabout

- A bike trail

On the heels of each anticipated or actual transportation upgrade came development.

- Half a dozen subdivisions with one-half to one-acre lots

- A couple dozen homes of the exurban variety (2.5 to 10 acre lots)

- A 26-home subdivision on 2.5 acre lots (down the street from our building)

- A hotel

- A multiplex theater

- A Walmart

- A gas station with car wash

- Several miscellaneous businesses and eateries

In the same period the natural world lost a few things.

- Tens of thousands of wild plants of a few dozen species rare in these parts and selling for $4 a pot at your local native plant nursery (if you can find them)

- A population of cream gentian, an extremely rare plant across the Midwest and denizen of an almost extinct ecosystem, oak savanna

- A distinctly pleasant drive, with woods closing around the road and gentle slopes leading away

- Woodland edges fringed with attractive sunflowers, dogwoods and plums, set against the aspens and oaks

- A grass-fed herd of cattle

- A goat and horse farm

- Several buildings around one hundred years of age

- Dozens of oaks approaching 200 years of age

The rare, savanna-dwelling cream gentian growing next to Highway 8 once upon a time–a casualty of road widening. Photo

by Kim Chapman

That makes for an interesting balance sheet. The human dominated space expanded, the natural space (to which people belong, though we always forget we do) shrank to compensate. This has been the way of the world for several millennia now, with no sign of stopping until the mid 22nd Century when, the United States Census Bureau tells us, the human population will stop growing. And roads, those ribbons of speed, those lassoes tossed outward as an extension of our inspirational will, those simple engines of economic activity and landscape transformation—the roads made it all come true. They were the advance guard, rushing forward to clear the way, or speed the onward push of a realm where what comes from us, the people, is what one mostly gets.

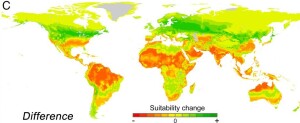

It doesn’t take much to understand how roads are the most civilizing force we wield—moreso than the missionary’s religious zeal to the heathen, moreso than the telephone and satellite television for the remote inhabitant, moreso than cell phones in the Serengeti. In a case most of us have heard of, tropical deforestation, you can see on satellite images from the 1960s to the present a perfect match-up between a new road and the jungle clearing on both sides of it…followed by settlements, cattle ranches, and soybean fields. On my commuting route, Highway 8, the abandonment of farming operations and appearance of for sale signs and subdivision placards happened simultaneously with the most recent road upgrade. For people wanting a country home, land became more valuable with the faster road to speed their commute to the Cities, and for others their property became less livable or usable with the faster road nearby—more noise and congestion now knocking at the front door.

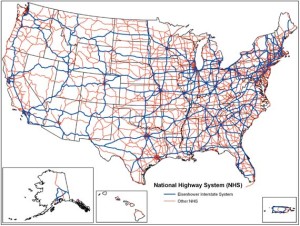

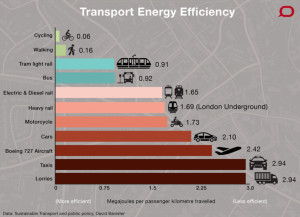

For about a century, from 1840s to the 1930s, railroads were our nation’s roads. Actual roads were in terrible shape by comparison…rutted, often flooded, narrow or steep, dangerous in hilly and mountainous terrain—as recently as the 1910s it took weeks to traverse the country by road. That all changed beginning in the 1920s when the “Good Roads” movement seized the imaginations of government planners. A slow disinvestment in railroads took hold, offset by a huge ramp-up in road building and road improvement. Engineering schools in Michigan—ground zero for the car industry—began an innovation and training jag that spread nation-wide and continues today. By now several generations of road-builders have perfected the art of laying down concrete and asphalt, erecting bridges, and designing for the most efficient movement of vehicles from point A to point B. At the risk of being labeled a curmudgeon (oh…I’ve already been labeled that?), I will say I’m not a fan of roads, but not for the reason you’d think. I like roads that are put in the right place, serving the right purpose, and constructed in a reasonable fashion to minimize damage to people and nature. What I don’t like, and what prevails today, is roads put in the wrong places, roads built in part to serve a narrow idea of what represents progress, roads that are over-designed or dully designed by rote standards applied in a one-size-fits-all fashion—reminding one that, if the only tool you have is a hammer, everything you fix looks like a nail.

Attending a conference a few years back, I met an energetic young man who had been arguing with the US Department of Transportation and the state of North Carolina about the re-routing of a major highway near Asheville. This is in the foothills of the Smoky Mountains. He and a partner had intelligently designed an alternate route which reduced the road length, reduced the amount of blasting and earth moving, preserved more forest and natural slopes (which in turn protects streams below those slopes), and still met the stringent federal safety standards. In other words, their road design would have saved money and nature. From the sounds of it, theirs was a losing battle. The imagination of those with their hands on the levers of power could not accommodate the vision of these two young men.

Woodland sunflower fringing a woods cleared for Highway 8 reconstruction. In pots, these would cost $4 each. Photo by Kim Chapman

When you speak with the road planners about their effects, they say, “Oh, no, we don’t pick winners and losers…we just respond to current and reliably predictable future growth.” This is not true. Perhaps they don’t intend to pick winners and losers, but the unintended consequence of their decisions is to pick winners and losers. Why is it so hard to believe that establishing a new or better way to move people and things around draws more people and things to it? This has been the history of transportation. Development nicely follows new or improved transportation routes when a route is penciled in on a map. This happened with the railroads. When they were being built in the Midwest, speculators used the maps of the future railroad locations to buy up land and sell it to settlers and business people from the East. If you look at where the towns are, they are strung along railroad lines at distances about equal to a half-day’s horse-drawn wagon ride…so farmers could get their grain to the railroad station in town and make it back home by nightfall.

Likewise in the interstate-building period…the placement of interstate highway interchanges contributed much to the shift in commercial activity from the center of towns to their edges. The hollowing out of Midwestern downtowns was helped along by fast roads that got you in and out of town quickly. Shifting the through-traffic to an interstate or major highway often precipitated a town’s death spiral, especially towns smaller than 10,000 people. (Towns lucky enough to have a college or a few major businesses did better.)

The counter proposal is just as true. Taking a recent example from my current home, Minneapolis-St. Paul, when light-rail transit lines were proposed, two or three years before they were built, developers began rehabbing the warehouses and building massive apartment buildings to respond to the inevitable demand for housing near the transit lines. University Avenue, the ten-mile long connecting road between the two downtowns, is hardly recognizable today compared to fifteen years ago—so many new buildings, upgraded restaurants and shops…so many more people walking the sidewalks. Transit picked the winners and decided the losers in the regional game of attracting people and generating economic activity, just as I-494 stimulated the third ring of suburban growth around the metro. The same thing with railroads 150 years ago…where the tracks went, villages grew, and where they did not, those villages faded away.

Several years ago I wrote a grant proposal addressing this issue. It wasn’t funded—the sponsors got skittish at the last minute. The gist of the proposal was that roads exist to serve people. The planners would say, that’s what we believe, too. Perhaps so, but the way that roads are planned suggests that the opposite in fact is true—roads are kingdoms unto themselves, planned and designed with a set of principles that have more to do with connecting point A to B using a universal standard that doesn’t apply to local conditions.

In other words, people must adapt to roads, as they are conceived of by people trained to build roads. Those same people are not trained to understand what makes a livable community, what preserves an ecologically vital place, what brings beauty to a space. They are trained to build roads, with the cultural, ecological, and aesthetic considerations tacked on in the process to meet regulatory requirements. My proposal was simply this:

- Design an ecologically healthy configuration of ecosystems that can withstand the buffets of change over the next century,

- Design an environment for people’s cultural and economic aspirations within that ecological framework, and

- Design a transportation network that supports the first two plans. In other words, roads would go to to the back of the planning line, not the front. Not the usual way road planning and building are done. No wonder the sponsors pulled the plug at the last minute.

Highway 8 reconstruction underway. The new road will go between the solitary tree in the photo’s center–once at the edge of the forest there–and the new treeline on the right. Gotta move that hill first. Photo Kim Chapman

If we built or upgraded roads using this simple approach, perhaps the regulations to protect the environment, culture, and beauty of our world could be scaled back. Instead, road building and improvement could actually be put to good use improving the environment, culture, and beauty of the world, rather than being an engine of degradation.

In a surprising burst of creativity, the US Department of Transportation during the Obama years attempted to do just that. The USDOT leadership convened a series of meetings with the leadership of all other federal government agencies to develop guidelines as if the ecological and cultural elements of the world really mattered. It laid out a planning framework in which roads would, indeed, be built and revamped with nature and human communities in mind. They called the initiative “Eco-Logical” because, of course, it was the logical way to go. (Great idea, but the name…ouch.) In any case, marketing caché aside, the Eco-Logical approach was a great start. Judging from what I’ve seen on Highway 8, it’s not taken hold yet.

The ideas in the Eco-Logical approach are pretty good. Among them: avoid damaging the environment by having good advance data and taking creative approaches to road construction; and use the construction project to improve the environment—clean up dirty road runoff, plant hardy natives, and restore habitat. All positive moves.

Until we fundamentally change how we view roads—making roads serve people and treat nature benignly, rather than force people and nature to adapt to roads—all will not be well. We have another hundred years of population growth and development ahead of us before our human family’s expansion greatly slows down. Will the result be more loss and degradation of the environment, disruption of human communities, greater long term maintenance costs which we cannot afford…or something better than that? I’m convinced we can do better, and I’ve got a couple more decades in me to watch that come to pass. Time will tell. – Kim