The circular blockhouse at Fort Snelling, defending against the noise of commuter traffic on Highway 5 where it crosses the Mississippi River. Photo Kim Chapman

September 3, 2007. I passed this morning a postage stamp piece of the original, authentic Minnesota. It’s just a little scrap of land wedged between two highways and the federal lands containing the Veterans’ facilities and other administrative chunks, all part of the former Fort Snelling Military Reservation established in 1805 by purchase of 155,000 acres from the local Dakota Indians for $4 million (2017 dollars), which was never fully paid, apparently.

As you drive this stretch of road you notice, if you’re paying attention, an oddly placed chain link fence. This is an old fence, perhaps from when Highway 62, my commuting route, was punched through in the late 1960s. When I first moved here thirty years ago, the little patch was mostly prairie grasses and sagebrush, and a succession of flowers starting in June with bergamot whose scent is the flavor of Earl Gray Tea, then black-eyed susans, drooping-petaled yellow coneflower, and finally the fall colors of goldenrod and aster. The eternal grasses of the tallgrass prairie stood there in profusion through the winter—copper-colored big bluestem and Indian grass, and the yellowish prairie cordgrass with its graceful arched stems waving in a decent wind.

None of that is evident now because a thick growth of box elder, ash, diseased elms, and shrubs has taken over.

Mysterious fence around the Highway 62 prairie is quite evident in this air photo kindly provided by Google Earth.

The reason I’m so obsessed with this patch of ground—besides the curiosity of a scientist in watching thirty years of plant succession—is that this place is a stone’s throw from the Mdewakanton Indians’ traditional place of origin. This whole area, the military reservation the US Army established on the order of Thomas Jefferson, a time when soldiers wore nearly brimless blue top hats, was the center of local Dakota civilization. There was a sacred spring, called Coldwater Spring by whites and Mni Owe Sni by the Dakota, on the bluff above the Mississippi River to which the soldiers moved after losing half their number to disease and starvation the first winter spent down by the river. When Josiah Snelling showed up in 1820 to build a fort, the soldiers had moved to the flat, open plains by Clearwater Spring.

The soldiers quarried the bluff-topping Plattville limestone to build the fort, and you can still see those ancient workings today along a bike path that sits on an old road between the fort and Minneapolis. Snelling’s lovely house for himself, wife and children looks east over the confluence of the Mississippi and Minnesota Rivers. From his back window he could see the hill the Dakota called Wotakaye Paha or Oheyawahi, and Pilot Knob by paddle-wheelers that steered by it. Loosely translated, it meant “hill of the relatives”, or “hill that is visited often”. This was a burial grounds as well as a place where Dakota met to discuss the important issues of the day and settle matters. Josiah may have had inklings, given the history of his country’s dealings with Indians, that in the year 1851, seven years before statehood, a treaty would be signed here that gave for $42.3 million (2017 dollars) some 35 million acres of Dakota land to the United States government—a bargain at less than 2 cents an acre. Between that not so great deal—much of the money was already spoken for by traders who sold Indians goods at inflationary prices on credit—and the Germans and Scandinavians who flooded the scene in the 1850s, topped off by the Civil War that caused the government to forget its treaty obligations to address more pressing matters—the tinder was laid to ignite the US-Dakota War of 1862. That event unleashed such sorrow from which the state has not yet recovered. You can read about this in the beautiful expository of Minnesota history by Mary Wingerd. Yes, there are villains and heroes.

From Wotakaye Paha, which I am near when I bike the Mendota bridge where the Mississippi receives the Minnesota River—at Bdote, the place where two waters come together—you have a commanding view up and down both big rivers and can see in the distance the white sandstone cliffs where the Kapozha Indian village was, up the Minnesota to the Indian town of Black Dog, and on some days spy the mists at the thunderous cascade of St. Anthony’s Falls where the little village of St. Anthony was built to cut logs and grind grain for the soldiers’ construction projects and sustenance. Louis Hennepin, the boastful Franciscan priest who made a name for himself in Paris with his travelogue about the Upper Midwest, was taken as a captive by the Dakota in the year 1680 and brought to the falls, which he named for a Franciscan friar and the patron saint of lost things and also of Hennepin himself. (The falls already were sacred to the Dakota, so giving it a Catholic saint’s name didn’t embellish it at all.) I occasionally bike the route of the portage he walked to view the falls—amazing how the past is still present, and not so long ago.

Bdote, where two waters meet…the Mississippi and Minnesota Rivers. Wotakaye Paha, or Pilot Knob, is the hill on the horizon, and Fort Snelling is just off photo to right, on the opposite bank. Photo Kim Chapman

Back to this little patch of prairie…on a map I saw briefly years ago, and which since has disappeared from the Internet, was marked the center of the Dakota’s world, its Garden of Eden. The place was a distance south of the little prairie, at the edge of the airport, on a rise of land in the plains. Now it is packed with little ranch houses and bisected by a big fence topped with barbed wire for national security reasons. It’s the Twin Cities airport, after all.

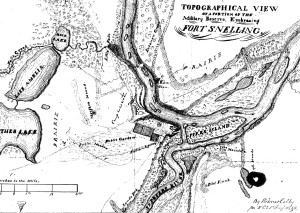

R. Jones Colby’s 1850 map of Fort Snelling and environs. Pilot Knob is southwest of the fort, and the spring where soldiers camped while building the fort is just northwest of the fort.

I had a close call there the summer after 9-11 when I got it in my head to drive the neighborhood and find the place where the Dakota people’s world was centered. I found the highest spot in the neighborhood and parked at the intersection of two streets, near the airport fence guarding the planes against another catastrophe—and naturally the neighbors called the police. Before the police arrived, though, I’d worked my way east and had just turned the corner by the Fort Snelling parade grounds when I spied them driving way over the speed limit, headed to where I’d been seconds before. Somehow they didn’t see me. I took that as a cue to leave. Back on Highway 62, I caught a glimpse of them racing down the frontage road in the opposite direction. I was spared, perhaps by the same Great Spirit the Dakota put their faith in.

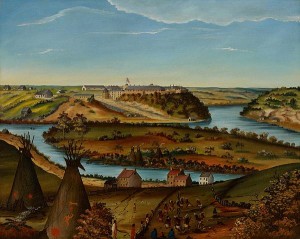

From Wotakaye Paha looking west to the fort. The Mississippi River heads upstream on the right, and the Minnesota to the left. The island is another important place to the Dakota, named Pike after the same Zebulon who never ascended Pike’s Peak, but did buy 155,000 acres there from the Dakota on which to construct the fort. Painting by Edward Thomas 1850. Collections of the Minnesota Institute of Arts.

I wonder what this all means, my mingling of the personal and factual, of the distant past and present day. I suspect that this is the last unturned piece of soil hereabouts, still holding the same carbon from grass roots which grew here 10,000 years ago—a deep, black soil that made the Midwest the breadbasket of the world. This organic-laden dirt, a few feet thick, created by millennia of lives that played out to their endings at this spot, is perhaps mingled with the blood and tears of a nearly vanquished people and occasionally the tears of newcomers who sympathize with their story. Good thing there’s a fence. – Kim