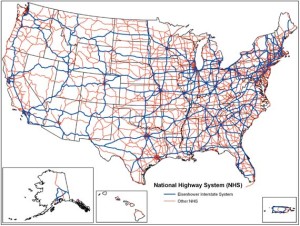

The US Highway System–interstates and federal roads–have got us covered, except for a few pesky white spots where people are few. Courtesy US Dept. Transportation

October 25, 2017. Years ago in a former job and former life, there was a man in the volunteer leadership of the organization I worked for who was a transportation planner and engineer. He was also highly placed in the Twin Cities transportation community. He and I hit it off and would talk about the topics of the day, one of which was public transit—buses, light rail, streetcars. Being a transportation expert who came of age in the car-driven planning era of the 1950s and 1960s, he saw no need to invest in public transit, and in fact felt that public transit was a dying form of transportation to be supplanted eventually I suppose by individual car-pods that would be controlled by computers, pick you up at your back door, and let you off at your destination. (And yet, now he seems prescient…as we stand on the threshold of self-driving vehicles.)

One of his arguments against public transit was that our cities had outgrown the need. Most people, he said, lived in suburbs where densities couldn’t support a cost-effective public transit system, nobody lived downtown, and the areas of urbanity in between were best served by car. I pointed out that higher urban densities justified investments in public transit just as great distances in rural areas justified investments in interstate highways. Interstate highways didn’t pay their way, I argued. User taxes—gas tax, special taxes on trucks—don’t pay the full cost of building and maintaining the road network; the rest is paid by general funds, making roads a type of public transport.

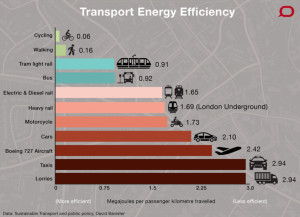

He would then counter with the cost per passenger mile to construct and maintain the different systems. His argument was always that cars were more efficient than public transit on a per passenger mile basis. This was long before $4 a gallon gas—when gas prices were as low as in the 1970s, adjusting for inflation. Back in the 70s, when I first started driving, we paid 25 cents a gallon at “gas war corners”. (Gas war corners: where two or three gas stations at the same intersection tried to undercut each other’s price. Everybody in that part of Dearborn and Dearborn Heights bought gas there.)

I couldn’t argue the point because I didn’t realize that the rock-bottom price of gas was subsidizing the low cost per passenger mile. And I didn’t have the presence of mind to point out that bikes, with no energy cost but your breakfast, were the most efficient way to move around. I also know now that, to use just one example, trains are much more cost-effective than trucks at delivering goods to market—a ton of freight can be moved 400-500 miles on one gallon of fuel. Sailing ships would be amazingly cost-effective if people would accept the extra couple days to receive their toaster from China. Trucks and cars, then, aren’t the cheapest way to move things around, they are just convenient at the moment.

If you want to be really efficient in how you use energy to get around, ride a bike or walk. If you don’t, hop a plane. (Missing from the picture..gondolas and catamarans, among other things.) Chart from Sustainable Transport and Public Policy (2009) by David Banister, from the intriguingly titled book Transportation Engineering and Planning, Volume II (part of the equally intriguing Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems).

At some point we wound up at the chicken-egg conundrum of new road construction. He believed that roads merely responded to trends, anticipating and serving future growth, while I maintained that they stimulated growth—my opinion was backed by a couple of decades watching the process unfold across the Midwest. We wound up at loggerheads every time. In my travels I’d seen the tell-tale signs of future road work—the black hoses laid across the roads counting cars, or pink wetland delineation flags—and a couple years later, a wider road appeared…or a new road or bigger intersection went in…after which development blossomed.

If we’d been talking a few years later, I’d have brought up Atlanta. In the late 1990s road construction in the city of Atlanta was effectively halted because the city had tried and failed to build its way out of traffic congestion. They had already installed two ring roads—the first in the 1950s and 1960s for inner ring suburbs, the second in the 80s and 90s to serve the second suburban ring because the roads around the first were choked with traffic. Atlanta planned to build a third ring road, but in 1998 the US Environmental Protection Agency, citing the region’s deepening air pollution problem, cut off federal transportation funds until Atlanta took a different approach to solve its congestion. As it had before, another ring road would simply cause development to leap outward and fill that road up, too, with extra emissions to boot.

I argued against a similar proposal here in the Twin Cities, in a 1990 Star Tribune Commentary. In the Twin Cities, the flickering flames of third ring road enthusiasm were doused by sensible people before the idea became a conflagration. Good sense prevailed also in the early 2000s, when the Twin Cities Metropolitan Council—an institution for pooling the region’s resources around transportation planning and other regional needs—introduced the idea of centers and corridors of growth—“smart growth”—as opposed to metastasizing growth across the region wherever roads or buildings would fit. Those centers of growth were to be on existing major transportation routes, where other ways of getting around could also develop—bus rapid transit, light rail, commuter bike routes, and ride-sharing lanes.

All this was yet to come, but at the time my colleague stuck to his guns, especially on the issue of roads not promoting low density development. Sadly, my friend died in the early 2000s and I could no longer annoy him with my arguments (or give him the floor to argue against my views, including this essay). I would have told him, for instance, that I am witnessing firsthand the transformation of a mosaic of forests, wetlands, pastures and cropland to an exurban suburbia of big homes and vast lawns after major road upgrades were planned and executed by the highway department using data from those little black hoses they place on roads . − Kim