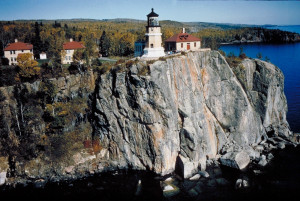

The Split Rock Light stands guard on a rocky headland of Lake Superior’s North Shore, warning ships away from dangerous waters. (Photo Dennis Adams)

June 27, 2015. I just got back from a family vacation to the Split Rock Lighthouse State Park—a perfect example of the interconnections between nature and culture. The park is at one and the same time a shrine to the heroic age of industrialism, a recreational center for kayakers, hikers and campers, and a refuge for all the many native species of plants and animals that need undeveloped land to thrive. The park commemorates a lighthouse built in 1910 to warn ships away from a dangerous shoal off the north coast of Lake Superior. At that time, the Iron Range of Minnesota was busily shipping millions of tons of rich iron ore to the blast furnaces farther south. According to the Minnesota Historical Society’s website, by 1901, U.S. Steel Corporation had 112 bulk ore carriers, making it “the greatest exclusive freight-carrying fleet sailing under one ownership in the world.”

The park visitor center is an excellent place to contemplate how natural wealth is turned into human wealth. Iron-rich rock which welled up from the earth’s crust a billion years ago was dug up in the late 19th and early 20th century and, using fossil fuels, turned into steel which was then used to build the rails and bridges, ship hulls and boilers, and the driving wheels of a new civilization’s transportation infrastructure, as well as the skeletal structure of its rising cities.

It is also a place to contemplate the stochastic fury of weather. Even coal-powered steel freighters were no match for a devastating November storm in 1905, when 29 ships were sunk or driven aground in western Lake Superior. As a result, business interests lobbied the government and the U.S. Congress allocated $75,000 to build a new lighthouse, perched on the top of a billion-year-old chunk of anorthosite and looking out over the vast expanse of America’s largest and stormiest freshwater sea.

A hundred years and some change after it was built, the lighthouse has been made redundant by radio beacons, automated lights and radar and sonar navigational equipment. But it provides a different kind of safety now. It is a haven for animals and plants which need protecting from the rapid development which has proceeded apace since the construction of Highway 61 in the 1920s. Just yards from the roar of that highway, hikers and campers have a chance to view original inhabitants of the land, such as flowering bead lily, columbine, the American toad, the grey tree frog, or the tiny boreal chorus frog. (My daughter Pippa, a budding herpetologist, spent every evening down on the rocks by the lake, tracking down frogs by their calls and taking their portraits—all these photos are by her). – Jim