I was sure I could boil 40,000 words down to 1600…but, alas, I couldn’t do it. So here’s the third installment of my musings on the Pope’s Encyclical, “On Care for our Common World.”

What is it, then, that will steer us away from a “compulsive consumerism” which the Pope says is “based on the lie that there is an infinite supply of the earth’s goods…”? Francis arrives at a solution to the ecological crisis little different than the one that Jesus taught two millennia ago to heal the wounds of society—an “interior conversion.” Simple gestures of kindness, a generous spirit, and tender feelings, practiced daily, will push back, says Francis, against the juggernaut consumerist engine and the media and markets that power it.

This is no large program, no marshalling of resources and manpower, no call to arms—it is something that each person must experience for him or herself. In the end, he says, it is a question of our dignity. Jim Armstrong, in the last essay of our book, Nature, Culture, and Two Friends Talking, points out that future generations will look back on this moment in history and wonder at our ignorance and unwillingness to break with “the logic of violence, exploitation and selfishness” as Francis calls it.

That is why it is no longer enough to speak only of the integrity of ecosystems. We have to dare to speak of the integrity of human life, of the need to promote and unify all the great values. Once we lose our humility, and become enthralled with the possibility of limitless mastery over everything, we inevitably end up harming society and the environment.

The opposite of the world view that Francis critiques is one where the joy of being alive is embraced by everyone, understood by us as something we have in common with all creatures, and is part of “a splendid universal communion.” The hard part is getting there—because it can only happen one soul at a time, as each one of us figures out what smoothes our furrowed brow, defeats our inner demons, and frees our spirit so that we, as if children again, find wonder and beauty in the people and world around us. Such an old idea—strange how easily it is forgotten—or unlearned more like it.

Toward the end of the Encyclical, Francis takes a side trip into the practice of saying grace before and after meals. For him this little ceremony that hits the pause button in our busy lives, embodies the spirit of thankfulness for life and creation and unites us with those who produced the food—a literal source of life—and helps us to remember those who each night go to bed hungry. I believe it—in our household we pause at the beginning of each formal meal to acknowledge a break from what goes before and after this moment of communion which, at its heart, satisfies longing for and enjoyment of a life as best as it can be lived. A life with less food than the body craves, or food that is not enjoyable to eat, is a poor life indeed.

I love this simple phrase of his: “Nature is filled with words of love….” For me, truer words were never spoken. In several essays and poems in our book, Jim and I give voice to this idea. There is a mystical experience at the center of living, but it is drowned out by the distracting cacophony emanating from our culture’s workings. Whether you believe in God or not, everyone senses something very large at the central emanations of the universe when they find connection to something in nature, or with another creature, a beloved, or even a stranger in a momentary courteous exchange. I can only explain it as, life wants itself. Life drives all before it, gravitates towards other life, and will not be extinguished. Even if only dimly felt when gazing at millions of stars, watching a bumblebee energetically rummaging around in a gentian, seeing a bluegill defending its nest in shallow water, or your pet dog saying something to you with his eyes—it is all about life talking to itself, wanting to be surrounded by itself.

Francis feels the connection between God and all living things as essential to living a full life. That’s because it is all about relationships—people to God, people to each other, people to nature. Forming and nurturing relationships makes a person grow up. Anybody with kids knows that, or with an elderly parent to care for, a dying friend—even an old Greek Revival house or a pet helps us to mature. Why? Because attention must be paid, the pace must be slowed, care must be taken, consequences weighed—or it all goes to hell. Mistakes were made, is a common afterthought when one doesn’t do the right thing out of concern for the common good. In the end, each of us cannot act in even small ways without creating society’s future. I think that’s the Pope’s main conclusion, and as an ecologist, I agree.

What do you expect from an Argentinian priest who spent much time with the poor, refused to move into the opulent papal residence, and lectured his colleagues on the contradiction of their lavish lifestyle? He is a revolutionary, of course, as Jesus was, and just as Jesus did, he is making some with a stake in the outcome of this debate uncomfortable.

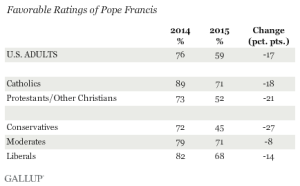

The Pope’s views are stirring the pot. David Brooks and a number of other commentators, while praising the overall thrust of the Encyclical, took Francis to task for his criticism of the economic system of capitalism—“the greatest engine for lifting people out of poverty that has ever been.” This and similar thinking—a friend of mine pointed out the Pope’s opposition to carbon credit trading and his failure to mention the more effective carbon tax approach to reducing CO2 emissions—signal a distrust of capital-driven free-market economics. His popularity is taking a hit for this and other ideas. In a Gallup poll taken a few weeks after the Encyclical was released, support among Protestants and conservatives had plummeted from the year before.

As Pope Francis works out an expression of “authentic freedom” through his writings, his poll numbers drop, according to Gallup.

For my part, he gets high marks. I think the Pope has got it right. In the last essay of our book, Jim and I come to the same conclusion as Francis—it’s all in our heads. Without that “interior conversion” to a new way of thinking and feeling about nature, other people, and our own life’s course, collectively we will remain trapped in the technological-economic bubble we have created over the last couple hundred years. Steering toward an ecological way of living, let alone lifting up the less fortunate among us, is simply too big a challenge, even for committed united groups of people, unless everybody on the planet rows the boat toward the same distant shore. – Kim