A snapping turtle in Port Austin, Michigan, just out of the water–notice the wet shell. Heading to a nesting spot? Photo Kim Chapman

August 1, 2019. I have a reverse commute—starting in urban St. Paul, driving southwest through the suburbs, then into the countryside of Spring Lake Township south of Prior Lake. It gets more and more pleasant the closer to the office I get. I might see sandhill cranes grazing in a mowed field, see an eagle fly overhead, or hear a loon call from the lake across the street. Perfect for a guy who needs to feel the thrum of life around him to feel good about the world.

The down side of a reverse commute for sixteen years is watching the inevitable creep of new homes and faster roads reaching, like the tendrils and leaves of a spreading vine, into the farms and fields of the southwest Metro. Sometimes in the annual cycle, I feel a pang of regret at the human enterprise a little more than others. The worst is mid-June to mid-July, when, having gathered enough of summer’s warmth at last, female turtles of all kinds emerge from the marshes and lakes where they spent the winter and walk up to a mile away to lay eggs in a sunny patch of ground. Then they walk back to finish out the year fattening up before hibernating again.

Though I love the summer warmth and easy feeling it brings, I dread this time of year. There’s always a turtle or two that I am lucky enough to spot, poised at a road verge, neck craned as if watching for a break in traffic—in which case, I stop and carry them to where they want to go. Which is what I did around the Fourth of July. There she was, a snapping turtle, wet mud and grass on her shell, neck out and watching the stream of traffic on 185th Street. That highway had been upgraded about a decade ago to a four-lane divided—average speed, 60-65 mph in a 55 zone—obliterating a host of native plants that had colonized the edges of the older two-lane country road. And now, with four lanes of speed incarnate to get across, the chance of safe passage for a turtle was much reduced.

I pulled onto the shoulder, blocking her from the dozens of vehicles passing every minute—rush hour density—and walked up to her. Snappers are the hardest turtle to move. The hawk-like beak is downright dangerous, but the hind legs with half-inch claws are almost as bad. You must grip them slightly back of the shell’s center to avoid the terrifying beaked mouth at the end of a very flexible, long neck, and just forward of where their strong hind legs can take a swipe at you. Even so, more than once those hind claws have clipped a hand and caused me to drop the turtle. I am very careful about handling them, so much so, that this time I decided to put the turtle on the lid of a bin in the trunk that held my field gear. It worked swell. I carried her (pretty sure it was a her since the females do the long distance traveling at this time of year) across four lanes of fast traffic to the driveway of a horse farm. I slid her off into the grass, waited a bit, and soon her head was fully extended and looking around, after which she walked slowing onward away from the highway towards a sunny, sandy patch of ground where the eggs would be laid.

I knew two things as I drove away—the hatchlings that survived the depredation of raccoons at the nest and of other animals as they wandered through the landscape, would have to cross this same road; and that she would, too. The odds were low that a hatchling would find its way back to the mother’s pond given the obstacles—a convincing argument for the seemingly profligate 15-50 eggs that might be laid in a single clutch. The odds also seemed low to me of the mother surviving the 185th Street crossing again. What she had done and would do was, to a person, a crazy mission of hope—to a snapping turtle it was biological imperative, which passes for hope in non-humans.

A week later I found her, dead, a quarter mile down the highway. How could I know it was her? It was the same-sized turtle, with dried mud and grass on the shell, and at about the same place as before. This time she’d walked to a high point of ground to cross the road and meet her end. A tire appeared to have clipped the front of the shell while her head was tucked since it wasn’t crushed. The shell was cracked and her head lay on the ground, outstretched, a bead of fresh blood at her nostril. The collision had just happened, it seemed. I carried her to the road ditch where, rather than bake on the hot pavement or be turned into a roadkill pancake, she would melt into the ground among the grass blades. Actually, a snapping turtle that is crushed by a car doesn’t turn into a pancake—rather the shattered shell of a snapper resembles a bundle of dropped straws—a testimony to the sturdy construction of the shell.

Big highway + rush hour traffic = dead turtle. 185th Street is a tough neighborhood. Photo Kim Chapman

I wondered what she was doing at the top of a hill, then remembered I’d seen this before. I encountered a snapper with a three-foot long shell at the top of a hill on 220th Street years before. It, too, had tried to cross a busy road in early July. Not a good idea, but it’s their best and oldest idea at that time of year. It just so happened that the fast road post-dated that ingrained behavior.

Why does the death of a turtle by vehicle matter? In the big scheme of things, with war, murder, starvation, wreckage from natural disasters, and other sadness abroad in the world, a turtle hit by a car is inconsequential. That a man, an ecologist, should bother to think about such things, might be called silly and unrealistic.

On the other hand, it is both symbol and outcome of our civilization’s style, as embodied by the drivers of the several thousand cars using 185th Street every day. Confronted with a turtle in my lane, my impulse is to stop and take it out of harm’s way. Most other drivers just don’t see the turtle, lost as they are in their human bubble of concerns and urgencies. They don’t notice the natural world because the press of the human world—their cares and schedules, families and friends, impulses and passions—crowd everything out and obscure their view as if a piece of gauze were pasted over their eyeballs. Another group, an unfortunate one, may see the turtle, but circumstance prevents them from saving it. The road is crowded and they are doing 65 mph—too dangerous to slow or swerve! Or they may see it too late and not swerve quickly enough, even if swerving is safe—and they replay the sad event in their mind the rest of the way home. Then there is the tiny minority that will swerve to hit the turtle—they like breaking things, because they themselves are broken somewhere inside. We can only hope they encounter turtles very rarely.

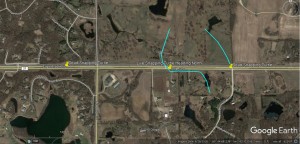

With wetlands and lakes north and south, turtles are certain to cross 185th Street. Two dead snappers were about a mile apart in early July. Photo Kim Chapman

So that’s it—meaning, wherever we put a fast road—the vanguard of our advance into ever-diminishing wild places—there will be death and mayhem. That is the inevitable, unintended consequence of our civilizing project. The wildlife crossing over interstate highways at Vail and elsewhere are a creative antidote, but are rare and expensive boons to wildlife. Deer and elk crossings are posted with signs, but turtle and small animal crossings go unnoticed and nearly entirely unsigned, except where the casualties are massive or profound—like the Blanding’s turtle crossings marked at Weaver Dunes in southeast Minnesota. (By the way, the antlers on deer signs are drawn backwards—a little known fact!)

Our civilizing project is so vast and relentless, though, a cure will only come when our minds make some room to consider, in every instance, the effect our actions have on the non-human-world–in other words, to pay just a little more attention. – Kim