A riffle beetle – a creature that lives in its own bubble – of air, at a stream bottom. Photo by Ed Engleman

August 15, 2017. This past month I was in Chicago and had a chance to visit one of my favorite institutions, the Field Museum of Natural History. I was especially eager to visit an exhibit entitled “Specimens,” a fascinating overview of the museum’s role in collecting, organizing and safeguarding over 30 million biological, geological, anthropological and zoological specimens. The exhibit was designed to explain that, although fewer than 0.1 percent of these specimens are ever exhibited to the public, they play a vital role in the ongoing expansion of our scientific understanding of the natural world.

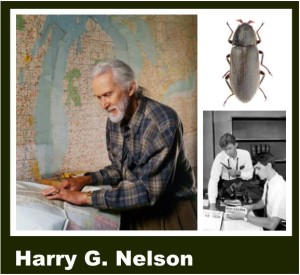

With this story, the exhibit did something unusual: it foregrounded the lives of specimen collectors themselves—those who travel the world, often in difficult conditions, to identify and bring to the museum the bewildering variety of animals, plants, rocks and artifacts that are stored in its archives. One collector in particular caught my attention: Harry G. Nelson, who spent his entire life collecting tiny dryopoid riffle beetles for the museum. Five hundred and twenty-five thousand riffle beetle specimens, to be exact.

There was a full-size photo of Nelson in his lab—an elderly man with a silver beard and ponytail, wearing the Pendleton shirt and wide-wale, high-waisted corduroys of a field scientist. Behind him was an enormous map of the Great Lakes region speckled with red paper dots; under his hands was a similar map. In addition to the myriad of boxes and jars of dryopoid beetles, this was Nelson’s other great contribution to science: bestickered wall maps. Over the length of his career he visited more than 6,000 streams in the upper Midwest and Canada—making careful notes of water conditions and of the presence or absence of riffle beetles. This care and detail would prove useful in ways he could not have predicted.

Harry Nelson at work, mapping riffle beetles across the Upper Midwest. His data are used by the US EPA to diagnose the troubles facing streams. Photo by the Chicago Museum of Natural History

Riffle beetles are tiny beetles that live at the bottom of streams and feed on algae. Unlike other water beetles, they do not surface to breath—they extract oxygen osmotically through an air bubble called a “plastron,” which they surround themselves with when they first enter the stream as adults and which they maintain all their lives as a kind of natural diving suit. Because of their unusual method of respiration, riffle beetles can only live in cold, oxygen-rich, and clean water: their presence or absence in a stream is therefore a good indicator of water quality. The power of Nelson’s maps therefore goes beyond merely describing the population distribution of an obscure, tiny insect—they are benchmarks of stream health throughout a vast swath of the country.

I was deeply moved by the patient work of a man who, with unflagging zeal, waded through thousands of cold Midwestern brooks and streams and rivers—no doubt swatting mosquitoes and black flies as he wielded his net and collecting bottles. When we think of science we often think of transformative figures like Darwin or Pasteur or Einstein—figures whose theories have changed the way we perceive the world. But such scientific giants only exist because of the vast body of data collected, evaluated, and catalogued by foot soldiers like Nelson. And whereas it is easy to see why it would be thrilling to be Darwin, we don’t perhaps quite appreciate why it would be important to be Nelson—or why it might be satisfying.

Nelson worked without knowing what good would come of his efforts. He no doubt felt the pleasure and excitement of the process itself—the opportunity to spend his days in the field, clomping through the bush in hip waders, carefully searching the riffles of streams for a tiny beetle whose life he became so intimately entangled with. But he also worked in the faith that the ongoing project of science was bigger than he was, something that had cumulative power.

People who cast doubt on science by and large have no idea of the actual work that goes into it—they don’t understand or appreciate the scale of this vast international human endeavor, or grasp the complexity of it. They mostly cast their stones at a few salient results, which they disagree with for pecuniary or ideological reasons. If they bothered to acquaint themselves with the massive accumulation of evidence those results are built on, or observe the patient, faithful labor of those who put that evidence in place, perhaps they would not so thoughtlessly seek to dismiss it. – Jim