An iconic Blue Marble shot of North America by Norman Kuring, 2012, courtesy of NASA and its Suomi satellite. The original Blue Marble shot was first taken in 1972 by the crew of the Apollo 17 spacecraft.

[I wrote this a month after Earth Day, 2017, forgot I’d written it, and wrote another essay on the same topic, which follows this one. The first is an essay, the next seems more like a poem. Interesting, the way time shifts perspective.]

May 22, 2017. A month ago on Earth Day, I gathered with about ten thousand other people in front of the St. Paul Cathedral and marched a mile to the state capitol. It was the March for Science and the first time I’d publicly made my political opinion known. Well…there were those commentaries for the Star Tribune, one on how to control zebra mussel spread with a lake quarantine program, and the other against a third ring road at the fringes of the Twin Cities suburbs which would not relieve congestion but only promote sprawl. In both I amassed facts, made a compelling case (I thought, anyway), left the job of politicking to politicians, and stayed true to my dispassionate calling as a scientist. Our reputation depends on not holding an unassailable point of view on a research question, but rather weighing the evidence and drawing a reasoned conclusion which the majority of one’s peers would accept as consistent with the facts. That is the way of science. (Ah, but…scientists have a point of view on lots of things, you say. The difference between them and non-scientists who write about science, is that scientists are trained to draw conclusions separate from their personal opinions, and to bow to the reasoned opinion of their peers who severely critique their work. It’s ok to hold an opinion about a theory–that’s called a hypothesis–but as a scientist you’d better be ready to change your opinion if facts don’t support it.)

The March for Science on Earth Day, 2017, brought out millions of scientists around the country who have cultivated a habit of making reasoned judgments based on facts and subject to the critique of other scientists. At this moment in our nation’s unfolding story, though, it seemed important to these millions to draw attention to something. One sign at the event summed things up nicely. “When the introverts are marching, something is wrong.” That’s the truth. Those people crowding around me, wearing t-shirts with “e=mc2” or the face of Bill Nigh the science guy, or Einstein, and carrying signs that a scientist would find amusing, like—“Empiricism now!”—these people would like nothing better than to stay in their laboratories, or walk their field plots, or take their lake sediment cores, and measure their atmospheric gas levels using a weather balloon—they’d like nothing better than to do these things, publish their papers, go to conferences, and be left alone. At this moment, though, they all sense something seismic had shifted in the cultural landscape, and that’s why they were here.

Scientists and friends gathered at the Cathedral of St. Paul, April 22, 2017. State capitol in the distance. Photo Kim Chapman

What was that shift that they sensed which drew them into the sunshine of a beautiful spring morning with fellow eggheads and science geeks? Maybe it started in the 1990s when science got caught up in the culture wars, a time when conservative think tanks and far right talk shows were changing the landscape of public discourse. What the marchers all around me sensed happening was that a determined group of people were trying to erode the faith that people put in scientists to tell the truth, or as much truth as can be told given the world’s complexity and our meager capacity to see, hear, and understand how it all works. Those culture wars, as many have pointed out, had their roots in opposition to the secularization and liberalization of our society, made visible in periodic skirmishes over tenets of Christianity as practiced by certain groups, and the scientific method. The Scopes monkey trial of 1925, for example, pitting godless Darwinism against the Bible’s seven day creation, is a classic case.

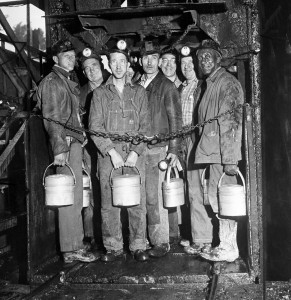

Let’s just say that this long-running altercation goes back centuries, and in our country, most obviously to 1909 when fundamentalist preachers and businessmen made their case for Christianity and against Darwinism in “The Fundamentals: A Testimony to the Truth”. Flash forward to the 1960s and ’70s and the enactment of laws that used scientific information to address urgent environmental issues. Those laws made rivers and lakes clean enough to swim and fish in; established sulfur dioxide emissions trading which eliminated smog that hurt the elderly, children and asthmatics; protected drinking water from dumped industrial chemicals; eliminated lead in gas and paint which effectively raised the IQs of urban children by several points; prompted an international ban on the chlorofluorocarbons damaging the ozone layer—a natural shield against cancer-causing solar radiation…I could go on, but you’d be happier if I didn’t.

Those actions affected business people who, already in the 1960s, had set their gun sights on what they believed was stultifying their earnings—high corporate income tax, personal income tax on high earners, laws favoring unions and opposing monopolies, restraints on international trade, and restraints on ingenious financial arrangements. To this laundry list of economic burdens was added “over-regulation”. Emboldened by the triumph in 1991 of a capitalist economic model over the Soviet’s extreme and incompetent socialist model, they mounted a full-court press in the 1990s and have pressed on vigorously to this day. Businessmen paid scientists willing to skew or selectively use data, and supported outspoken individuals who were only too happy to bring worthy environmental laws under the umbrella of over-reach and over-regulation by a government intent on constraining liberty.

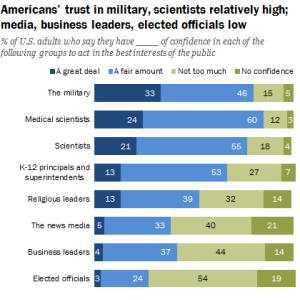

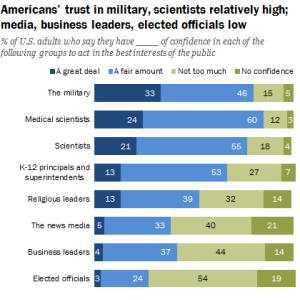

Once those elements were bound together and that story told over and over, a small but measurable part of the voting public saw scientists as biased with an agenda opposed to liberty, if not socialist in its intent. (Despite the galvanization of opposition to science, the majority of Americans still view scientists as mostly acting in the public interest.)

Most Americans still believe scientists mostly act in the public interest, but a solidifying group of voters and the people they elect increasingly do not. Pew Research Center poll, April 2017.

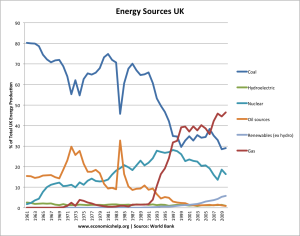

Calls for climate change action only made it worse. Most of the oil and gas industry, and companies dependent on fossil fuels but unable to see a path forward to other energy sources, opposed investment in alternative ways to power America’s industries, electrical grid, and transportation network, and any move away from fossil fuels. Conservative think tanks, conservative talk show hosts, and certain chambers of commerce carried the banner. Despite the sometimes distant effects of climate change (it will be a few decades before sea level rise combined with storms bankrupts the insurance industry), it is not a bad thing to shift to renewables. After all, they represent cutting edge technology, their future aims toward cheap and low-polluting energy production, and they will eliminate entanglements with oil-producing countries opposed to an open, democratic society, like Russia, Venezuela, and most Middle East nations.

One telling example of how science is made suspect for millions occurred in a Rush Limbaugh session where Rush questioned NASA research about a former ocean on Mars. Evidence for water on Mars, including once vast amounts of surface water, is pretty convincing. There remains on Mars enough frozen water to cover the planet. Rush’s incisive rebuttal to the claim of a lost ocean was, “How do they know that!?” He accused NASA of falsely alarming us by saying runaway climate change will eliminate water on Earth as it did on Mars. He went on…“They’re just making up the amount of ice in the North and South Poles, they’re making up the temperatures, they’re lying and making up false charts and so forth. So what’s to stop them from making up something that happened on Mars that will help advance their left-wing agenda on this planet?” Yes, the question is still open as to whether the hypothesis of a Mars ocean is irrefutably true, which is what separates science from belief or bluster dedicated to a single truth. Given the weight of evidence, though, it’s reasonable to assume there was an ocean on Mars, but you’d have to read the evidence yourself to know for certain. On the other hand, all Rush has to do to convince his millions of listeners—and everyone continuing the conversation at kitchen tables, Main Street cafés, churches and social gatherings—is to say “How do they know that!?” and all is suspect. He and his like, including past and present authoritarian regimes, know that repeating a falsehood thousands of times can shift public opinion.

One event in particular is a textbook example of how the impartiality of the scientific process and motives of scientists are called into question. In what some call Climategate, a hacker stole emails from the University of East Anglia, a climate change research center. The head researcher there, Phil Jones, was trying to combine a graph of tree growth rates with temperature measured by thermometers. Tree growth data and temperatures are correlated—warmer temperature produces wider annual growth rings because the growing season is longer and trees can lay down more cells in that period, thickening the annual growth rings. Cooler periods produce narrower annual growth rings. From 1880 to 1960, tree ring width largely followed temperature swings. Since 1960, however, tree growth has slowed while temperatures have gone up. Scientists in the field all know this—it is no secret (see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Divergence_problem). Going farther back, historical tree ring data matches other temperature indicators, like ice cores, quite well, and so it is a reasonable proxy for prehistoric and modern temperatures—until 1960.

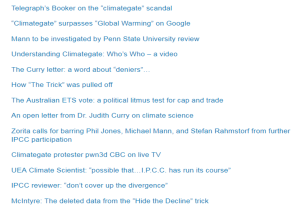

In one of the hacked emails, Phil Jones told a colleague how he was going to present in a graph the recent divergence between measured temperatures and tree ring data. If you want to read this yourself, go to https://www.skepticalscience.com/Mikes-Nature-trick-hide-the-decline.htm. In once sentence he said he’d use a statistical “trick”—not a trick at all, just his colloquial expression for a statistical tactic—which ended in the phrase “to hide the decline,” meaning the decline in tree growth rates. Recipients of the hacked emails revised the sentence to show nefarious intent: “a trick to hide the temperature decline”. Those words were not what the email said, but they were picked up verbatim and spread widely. The scientists were found blameless in subsequent investigations in the United States and Britain (see the Wikipedia entry on this, at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Climatic_Research_Unit_email_controversy).

Screenshot of a climate change skeptic’s website–with links to topics fanning the flames of false controversy.

For many, however, this was the smoking gun which proved that climate change was a hoax concocted by scientists intent on chaining American industry and its people to a poverty-stricken and limited future. Nobody need look at evidence, nobody need balance the evidence and reach their own conclusion. Climate change skeptics found the evidence, disseminated it widely, and for many it is now indisputable. Some of my relatives cite this moment to reject the entire concept of climate change. For them Climategate is a foundational truth propping up other evidence they’ve gathered from Internet sources, many supported by some in the fossil fuel industry and by conservative funders. That version of climate science seeks to refute the evidence that rising atmospheric carbon dioxide is paired with increases in temperature and water vapor, which is linked to certain unfortunate weather events around the globe, and that people are in part responsible and will experience economic and emotional harm that will increase over time.

The problem is that few have the time, patience or background to understand what really happened. The science has advanced to a point where ordinary people cannot engage with it. Just reading the Wikipedia entry about“Water on Mars” would take an ordinary person an hour. More urgently, there’s so much technical background you’d have to accumulate over a lifetime to grasp most of the concepts, it is just hard to understand. This is a problem for our society. The cultural-economic-techno bubble we’ve created to insulate ourselves against the ups-and-downs of the natural world is now so complicated that it takes a legion of experts to understand, operate and maintain it. Think of the economic system we’ve created—it’s no longer Joe trading Jane one sheep for two bags of wheat, like in the Settlers of Catan. It’s now about derivatives and futures and mortgage-backed securities and annuities and hundreds of other financial instruments, as they are called, to make and grow money. Medicine is becoming more complicated as we dig into the cellular, molecular, and genetic basis of biological function, and manipulate the body at the level of atoms, using tiny robots we create from atoms. We plow our fields and apply our fertilizers and pesticides using lasers, GPS systems, and computers. Hardly anybody can work on a car anymore—you can change tires, brake pads, oil and filters, but that’s about it.

Science is where our life-supporting technology starts. Science is the demon and savior at the same time. I suspect this is what my fellow Americans are unconsciously reacting to. No one person can understand it anymore. Leonardo da Vinci may have been the last to master all the sciences. The lay people who practiced science regularly lived in the 1700s, holding science parties on a Saturday night, playing with nitrous oxide which dentists now give you to relax. Fun was had with the repelling power of magnets, in extinguishing candles by pumping the air from glass bell jars, or with any number of interesting experiments done in the home. I was just at an exhibit at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts—an 18th century Science Salon could have taken place in the room where we stood. It looked so quaint, the various mechanisms and objects of science in an ordinary sitting room of the day. Imagine people like you and me doing science experiments at home on a Sunday afternoon, entertaining ourselves and guests. The closest thing to that now is the High School science fair with volcanoes made of vinegar and baking soda—no longer an award-winner , with top honors instead going to statistical tests of product performance or experiments with light refraction and wavelength detection.

On an emotional level, we have 95 percent of the country’s population who are not science people being bounced around inside this cultural-economic-techno bubble we’ve created and hardly understanding anything about it. “Why am I getting jerked around all the time?” they ask their neighbors. And then you have someone tell them that regulations scientists spawn with their so-called research findings are in fact in service of socialism, or crushing America’s entrepreneurial spirit, or just born of a gleeful petulance to control the world—you come to believe science is a humbug, to corrupt a phrase from Ebenezer Scrooge.

Now we have the science wars come to a head with the election in 2010 of an anti-science group in Congress and then an anti-science president in 2016 (or perhaps these groups are anti-science to the extent it benefits them politically). Ergo…the Science March. This and all the rest I touched on here is the seismic shift scientists sense has occurred, and they decided to march.

I’m walking on this beautiful spring morning with ten thousand of my fellow Americans, making a point. What is that point we’re making? I suppose it’s to tell those in power there are a lot of us out here who’d like the facts to speak for themselves. Feel free to disregard those facts, but tell it like it is—we disregard them because we can’t afford to pay attention to them right now. I can accept that. Tell us that we’d rather reduce corporate taxes and expand the military because we want our economic part of the bubble propelled forward by large corporations and the military-industrial complex, because we understand how to do that. That’s a political decision. To urge the case that science itself is suspect, and that scientists themselves are in service of their own nefarious ends…that is ridiculous. I marched to reassure myself that there are people out there thinking about science as I do, a source of enlightenment and a way to uncover the mysteries of the universe, and in some ways, discover the mind of God, or whatever you hold as the greater power behind it all. – Kim