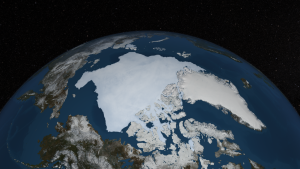

In Army-speak, this is a Landing Ship, Tank (LST) which helped win World War II, disgorging a tank. This one landed in Sicily in 1943. Photographer unknown.

June 7, 2017 (Winona Daily News). Over Memorial Day weekend I watched “The Longest Day,” the 1962 film about the Allied invasion of Normandy in World War II. I was interested in seeing it because I have recently been revisiting my grandfather’s role in the event.

He was not a soldier: he was a crane operator at the Evansville Shipyard on the Ohio River, which was put in place in just a few months in 1942 specifically to make Landing Ship Tank (LST) transports. LSTs were crucial to the war because they were able to land troops and vehicles on beaches, thanks to their innovative bow design.

The Evansville Shipyard was an example of the industrial organization that stood behind the Allied victory: as soon as America entered the war, virtually the entire economy was converted to the single purpose of defeating the Axis powers by turning out arms and materiel for the battlefield. The Evansville Shipyard converted a heretofore rather sleepy Indiana town into a major naval facility that, at its height, turned out two 300-foot ocean-going vessels per week. It employed 20,000 people, both men and women.

Nor was that the only production facility in Evansville: my grandmother worked in a factory that had been converted to make P-47 Thunderbolt fighter planes, and my great-grandfather worked in the Chrysler plant that had retooled to make 45 caliber ammunition. The overall population of Evansville swelled from 21,000 to 64,000 people almost overnight as people from all over the region flooded into the city for war work.

The effect on my family was immediate as well: many of them were finally able to buy houses (and in my grandfather’s case, a farm) and thus were pulled out of the cycle of poverty that afflicted so many working people in the first half of the 20th century. It is an oft-cited fact that the coordinated industrial efforts of World War II ended the Great Depression, and this was certainly true for my relatives.

I mention all this because on June 1 Donald Trump announced he would withdraw America from the Paris Climate Accord, claiming it was a “bad deal” for American workers. He cited questionable statistics (derived from highly disputed reports) that claimed any effort to fight global warming by decarbonizing the economy would put Americans out of work and transfer wealth from the U.S. to the rest of the world. This decision was in line with his “America First” agenda.

A clever graphic designer slipped the iconic tower into a leaf shape as the logo for the 2015 UN Climate Change Conference in Paris. It appears a leaf-eating insect has embellished the design, but what the divot means is unclear.

Many of the same arguments were of course made against entering World War II — in fact, Trump’s slogan “America First” is derived (via Pat Buchanan) from the anti-war movement of that time. But Pearl Harbor changed all that, and the net result of America’s militarization was the material prosperity that characterized the 1950s and 1960s—nostalgia for which obsesses Trump and his voters. As the sole standing industrial power after the war, America was bound to prosper; but the sense of shared sacrifice that characterized the “Greatest Generation” was also a factor. That shared sacrifice is exactly what is missing in our recent wars, which are fought by a tiny minority of Americans and are paid for by debt. It is important to remember that the tax rate on upper incomes during World War II was 94 percent.

Trump ran on a populist economic platform and then quickly betrayed it as soon as he entered the White House — bringing in the same Wall Street financiers who helped ruin the economy in 2008, and advocating the same tax policies that the Republican neoliberal elites have been trying to achieve for decades. His plans complete the redistribution of income upwards that has been going on since 1980, as the programs and tax policies that built the middle class mid-century are abandoned in favor of the laissez-faire economics that prevailed before the Depression. His claims that he wants to reclaim the prosperity of the postwar era are ersatz nonsense, of course. His plans for infrastructure investment are basically giveaways to private capital; these will not slow the decline of the American working class but will instead benefit wealthy communities and continue to privatize public roads and bridges.

By contrast, as Kate Aronoff recently reported in The Guardian, “… any reasonable solution to climate change will require massive amounts of job creation, putting people to work doing everything from installing solar panels to insulating houses to updating the country’s electric grid to nursing and teaching, jobs in two of the country’s already low-carbon sectors.” She quotes climate scientist Kevin Anderson as saying, “If you are genuinely serious about shifting to a low-carbon society within the timeframe we have, then it is an absolute agenda for jobs… You are guaranteeing full employment for 30 years if we think climate change is a serious issue. If we don’t, we can carry on with structural unemployment.”

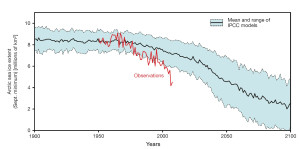

The biggest lie Trump told in the Rose Garden, just a few days before the 73rd anniversary of D-Day, is that Americans are not threatened by climate change. Like the America Firsters before him, he wants us to believe that America can be great by ignoring the moral and existential imperatives of our time. Every nation in the world — excepting Syria and Nicaragua — is in the Paris Accord, and this is because the dire effects of climate change do not respect national boundaries. A risk to all is shared by all, and the solution must be collective as well. Trump’s isolationism is essentially a denial of this shared vulnerability, and shared responsibility. It is a pose he shares with most Republicans but with nobody else (no other political party in the world denies the imminent peril of global climate change).

Everyone but us is now in the fight. The imperative is real, so are the benefits. We stand at the crossroads of history, and the hour is late. – Jim